ME & LITTLE C

- robertcocuzzo

- Jun 18, 2019

- 6 min read

My daughter had just turned four months old when I was diagnosed with cancer. Any cancer diagnosis is shocking, but I felt particularly blindsided by the news. After all, the lump on my thyroid had been biopsied a half a dozen times since it was discovered a decade earlier while I was in college—and the results always came back benign.

.

The mass had been growing steadily over the years, but still my endocrinologist said we could just either keep monitoring it or just have it removed. Ultimately, it was my wife Jenny—newly pregnant at the time—who insisted that we get rid of it. Had she not, I would have undoubtedly left it alone.

.

Two weeks after having it removed, I reported to my surgeon’s office for my post-op appointment. Cancer wasn’t on my radar at all. In fact, my only concern was whether she was going to allow me start exercising again. Upon entering, she didn’t even glance at my incision. She pulled up a stool and hit me with the news like a punch square in the face that instantly makes your eyes water.

.

“We got the pathology back...and...you have cancer,” she said, inflecting her words almost as a question, as if she herself couldn’t believe it. “There are three types of thyroid cancer,” she continued. “The most common is papillary. It’s very treatable.” I took a breath. “Unfortunately that’s not what you have...”

.

My life halted. Instantly. I could feel the world stop spinning. I could hear time. The silence of the exam room bristled with a faint crackle like the sound snow makes when it lands on your jacket while you’re riding up a chairlift. The doctor continued to speak, spelling out the steps ahead, but I honestly don’t remember a word she said. My mind was utterly consumed by my wife and my daughter—the very thought of them was so heavy that it knocked out my senses like a busted traffic light.

.

The surgeon rose from her stool and began examining the incision across my throat like a consolation prize. “You heel well,” she said, trying to change the subject. “So how old is your daughter?” The question cracked a hole in my state of shock and let loose a deluge of emotion. It was the first time I’d cried since the moment my daughter was born.

.

The car ride home was surreal. The last thing the doctor told me was: “Don’t Google it.” That really wasn’t a problem considering I couldn’t remember what kind of cancer I actually had. The real problem tumbling in my mind was breaking the news to Jenny. Our lives were bursting at the seams with a happiness we never knew existed.

.

When you have a baby, your perspective on time changes. Looking down at my little daughter, I could suddenly see into the future. Her first day of school. Her first dance. Her first love. Her first loss. It was such a profound thought that in this little being was a whole spool of time was only beginning to unravel. And yet now my spool felt like it was getting cut short.

.

I pledged to myself on the ride home from the hospital that I was going to take this challenge on with positivity. That’s the first thing I told Jenny. An absolute barrage of light would pave my treatment, whatever that might be. And with that approach, I also didn’t want to tell anyone outside of our immediate family, at least not yet. I can’t fully grasp the impulse for privacy, but perhaps it was in knowing that in recounting the circumstances to people would only offer more opportunities to put chinks in my optimistic armor.

.

That night was the longest night of my life. Lying in bed, I was tormented by the thought of not being there to see my daughter grow up. The mental anguish spread through my body. My legs and back cramped. My neck stiffened. Twisting my bed sheets into knots, I tried not to think about my wife and baby. Every time I did, I’d instantly tear up.

.

Instead, believe it or not, I thought a lot about Lance Armstrong. I pictured him with that scar running down his shaven skull, pedaling a stationary bike by his hospital bed. Say what you will about Lance—cheater, doper, bully—you can’t deny the fact that the guy willed himself from the brink of death back to living his ultimate dream. He raised a huge middle finger to cancer and I took a weird solace in that defiance.

.

Most of all, though, I became intensely aware of the temporality of my life. It all suddenly felt so short, so unfinished. I’d always pondered what I would do in a situation like this. Would I quit my job and live out the rest of my days in a perpetual state of hedonism? I realized quickly that that didn’t hold any appeal.

.

Rather, I wanted to hold and savor every moment. My life now felt like one of those bags of peanut M&Ms I used to eat on the train ride home from high school everyday. Back then, I was able to pace out the entire bag—methodically eating each M&M—so that it would last all fourteen stops on my way home. Now it felt like the train had been derailed and all my remaining M&M’s had spilled onto the tracks before I got a chance to eat them.

.

The day after my diagnosis, our apartment became a buzzing command center. Jenny mounted an offensive to getting me in front of the best doctors in Boston immediately. “In sickness and in health” took on a whole new meaning that day. Watching my wife call one doctor after another, between Googling treatments and haggling with insurance, I knew deep in my bones that she kick every single door to splinters to get me well again.

.

Having lost faith in our original medical team, we pushed for second opinion. But the doctors were booked out for weeks, and the gridlock of the medical establishment was becoming poignantly clear to us. Ultimately, it was a call to my boss Bruce that changed the trajectory of my care.

.

Within minutes of getting off the phone with him, we were in touch with one of the top oncologists in the country. Although I’m eternally grateful for this help, it also made me consider how many people must get pulled through the medical machinery when they don’t have someone advocating for them.

.

After reviewing my pathology, the oncologist called and gave us a clearer understanding of what we were dealing with. Though I had a more aggressive form of thyroid cancer, known as follicular carcinoma, the prognosis looked very promising. The first step would be to go back into surgery and have the rest of my thyroid removed. Six weeks after that, we could start running tests to see if the cancer had spread anywhere. If that were the case, a highly effective treatment called radioactive iodine would likely be administered. We started breathing again.

.

So began a six-month journey that continues to this day. In two weeks, I will go in for a full-body scan to see if the cancer spread anywhere. Based on my blood tests, the doctor said it is highly unlikely that we’ll find anything. We opted for the scan for the peace of mind. Much like with the initial surgery to remove the nodule, I’m doing the scan mostly to make my wife happy. But as I learned, she definitely knows best.

.

I feel deeply uneasy sharing my story. First and foremost, my experience has been monumentally less challenging than those who are truly battling cancer. I had lowercase “C” cancer. I didn’t fight it—I just dealt with it. And I would never want anyone to think that I’m comparing my journey to that of the real heroes I saw during my short visits to cancer wards in the city. Moreover, I am not fishing for sympathy. Since I made up my mind while driving back from the doctor’s office that day, I remain boundlessly optimistic that I am going to be perfectly fine.

.

So why am I sharing it now? Two reasons. First off, tomorrow I’m moderating a discussion with author Charlie Graeber about the new frontier of cancer treatment happening through cutting-edge immunotherapy. Ironically, I was reading Charlie’s book right before I got my diagnosis. With that in mind, I plan on mentioning my own experience as a prelude to our talk tomorrow, which is part of the Nantucket Book Festival. I’m sure there will be some of my friends in attendance who I haven’t told this story to yet, and I wanted to share this so they might understand why I didn’t.

.

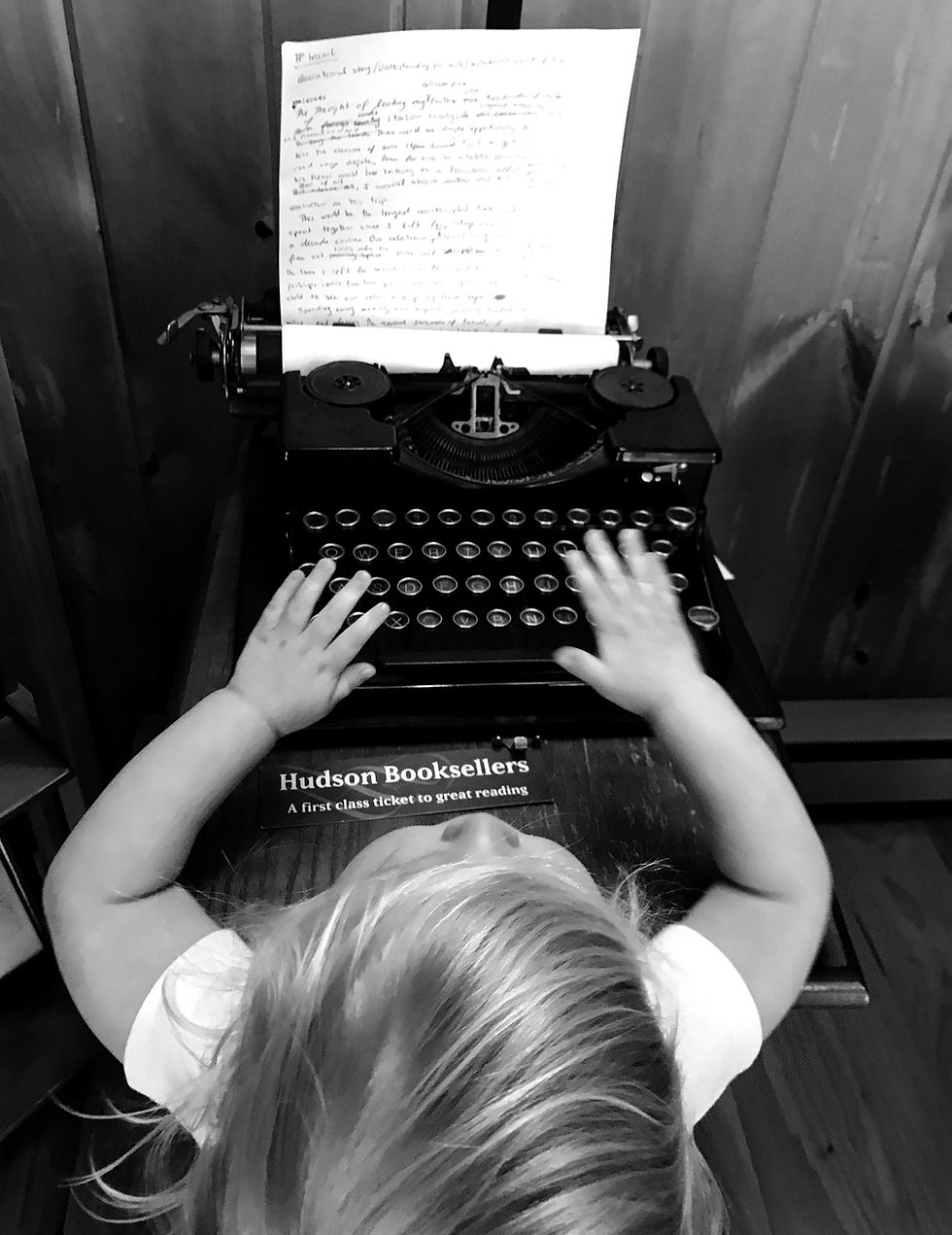

The second reason is far more personal. I fear I’m beginning to lose the perspective that I had the day of my diagnosis. I’m drifting away from a mindset that viewed life as ever fleeting. I’ve started to allow the day-to-day onslaught of meaningless stress to cloud my vision again, shrouding what is truly important. As I feel better and better, I’m beginning to forget how temporal life felt not that long ago. And so perhaps in putting pen to page today, I’m trying bear witness to the fact that we are all terminal patients, and we must remember to live accordingly.

Comments